Physical Address

Block 308 DBM Plaza, Wuse Zone 1, Abuja, Nigeria

+2347062940253

Physical Address

Block 308 DBM Plaza, Wuse Zone 1, Abuja, Nigeria

+2347062940253

I had my reservations about how a Western institution such as London’s V&A might try to narrate the histories of African fashion. I’m a “Born-Free” Black, Xhosa South African, from a country with 11 other tribes that each have their own histories, dialects and ways of sharing and preserving knowledge and culture. I’ve seen what happens when you try to homogenise these cultures into one big “Rainbow” quilt – it’s not very convincing.

Full credit, then, to the curatorial team and lead curator Dr Christine Checinska. I had feared the V&A might retroactively attempt to right, and rewrite, the pervasive wrongs of Britain’s history. I had also feared the clumsy use of broad-stroke storytelling. But a text at the beginning of the exhibition served as a disclaimer – and perhaps a challenge by the curatorial team to the museum – positioning the exhibition as a starting point rather than a final statement.

I agree. Now the V&A has set the stage (and challenge) for itself to progress to telling stories about Africa that are regionally and culturally nuanced – in the same way that it might explore the French Revolution or the Rococo period in European art history.

I have consistently seen Africa written from outside of it, according to the myth and exotification of the Western gaze. I have digested outdated textbook definitions of ideas and movements authored by Western voices. There’s a lingering refusal to process African art as art, rather than artefact, bound up in curiosity cabinets. We’re represented through the unchanging, “othered” lens of the “primitive”, lodged in the past.

Image Courtesy of the V&A Museum

But let’s turn to the detail of the exhibition. Draped head to toe in Rich Mnisi, the dancers of Lakin Ogunbanwo’s “Who Dey Shake” were the first details I saw of Africa Fashion, projected onto the domed ceiling of the V&A. I felt a tinge of excitement.

Africa Fashion articulates well the key role of fashion as an archive in itself; the ultimate time-keeper and a vehicle for memory, cultural inscription and communicating renewed identity, and political belonging. Dress and textiles have long illustrated selfhood and the things that people hold near and dear, such as education and a sense of national rebirth and pride in moments of independence and revolution. Where Africa’s academics, intellectuals and political leaders took on the risk of communicating with their words, dress – cloth, in particular – communicated those concerns on a vernacular level.

There’s a comment that resonates: “Cloth is to Africans what monuments are to Westerners.” Cloth is a consistent and ever-evolving presence – from adaptive traditional dress practices to the Nelson Mandela-embellished Kanga cloth that an auntie might wrap around her waist. It has shown up throughout the 20th and 21st centuries as a conduit of African contemporaneities, introducing new forms of national dress that test the boundaries of tribalism. Through cloth, African communities complicate the story a little, foregrounding innovation and lateral, cross-cultural/trans-national exchange (by the way, the absence of Shweshwe, a printed, dyed cotton fabric widely used in southern Africa, was a missed opportunity).

Image Courtesy of the V&A Museum

Dr Christine Checinska and the curatorial team of the exhibition sought to narrate an African continent that has a complex, cosmopolitan history in which African people and cultures have migrated and informed one another for centuries. The exhibition illustrated a narrative of trans-national cultural exchange by touching on the landscapes of music and print media, which embodied the sense of optimism that underpinned the era of independence on the continent. It explored the idea of African fashion existing beyond the colonised national borders and divisions of East, West, North and South, an approach that resonated with me.

Some key words in the exhibition catalogue: “Even in a bold and colourful dress, there is also the quiet of a coming together. That possibility that we, all of us, can know one another.”

There’s something emancipatory about the possibility of saying no to the colonial borders that have thrown our varied communities into the chaos of tribalism and xenophobia. Twentieth century designers Shade Thomas-Fam, Chris Seydou, Naima Bennis and Alphadi were among the key names chosen to reflect the diverse and global influences of African designers.

Image Courtesy of the V&A Museum

There could have been much more on the vast and varied East African fashion histories, as British-Somali Diamond Abdulrahim, who joined me at the exhibition, noted. “I recognise it’s a near impossible feat to capture the richness and variety of the African continent in any field, let alone fashion but it’s unfortunate that even within the paradigm of Africa certain geographical regions are privileged over others,” she says.

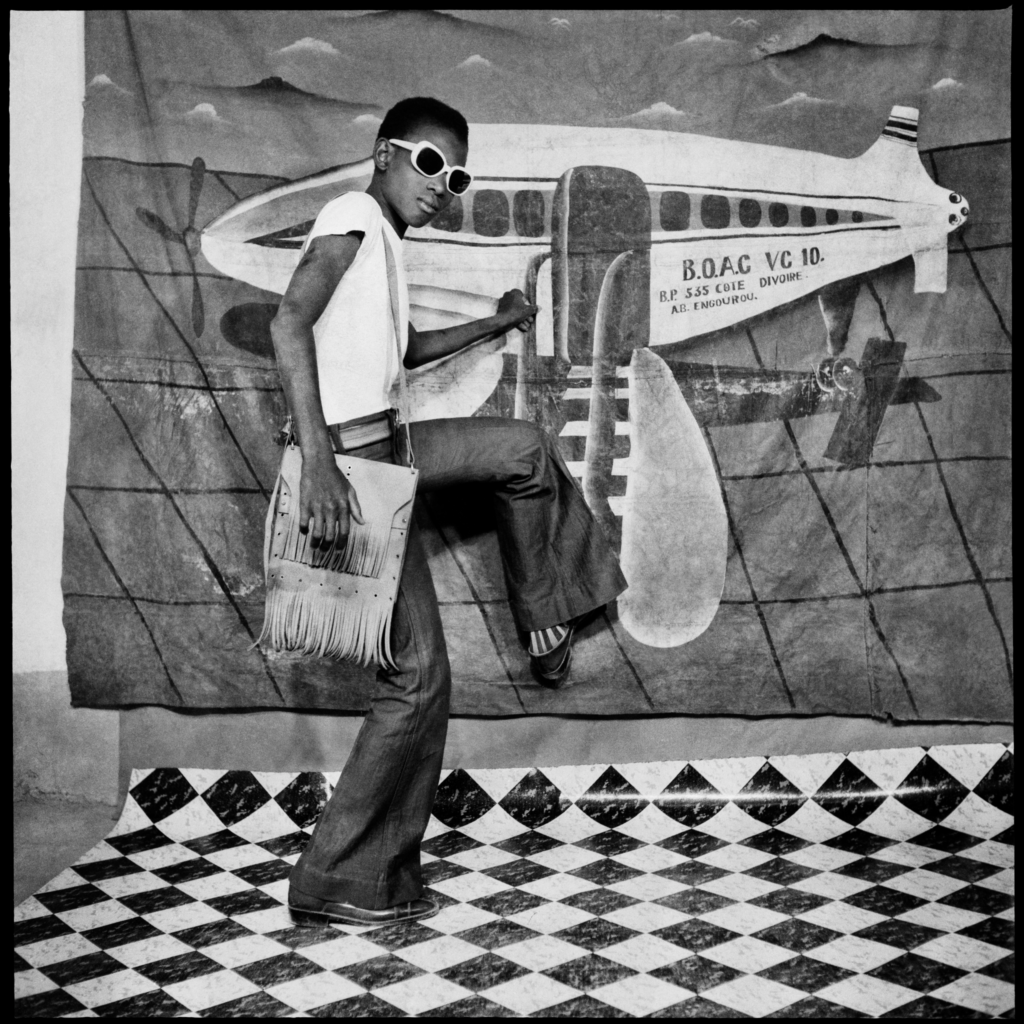

The recurring theme of self-authorship shifts in form, communicated in the exhibition through clothing, jewellery, the body and the photograph. Though the photography section favours West African stories, it felt nostalgic and familiar, reminding me of my own parents’ and grandparents’ photo albums, and their relationship with the camera as a documentary instrument. Conversations that I have had with my family around photography seem to open doors for an almost romantic remembrance of difficult times. My mother once explained to me the enfranchisement, status and personal economic progress that owning a camera tokenised for herself and her parents. Through self-produced/home-made fashion photographs, individuals turned the lens on themselves, imagining themselves as jet setters.

The notions of “cool” that they asserted are well-represented in the African diaspora’s western fashion histories, but tell the story of an entirely different relationship with fashion in Africa during the post-independence era. The bold showing off that one could do in the cosseted space of the photo studio could make you a target in public. It was a means of speaking and writing when either one could land you in detention. I was reminded of old photographs of my uncles in front of their cars and workplaces; making a show out of adjusting the volume on a radio, just to show their technological savvy; in their church uniform holding hymn books. My mother, a township pageant princess in her teenaged years, permed and producing high-flash recreations of a model’s headshot.

Image Courtesy of the V&A Museum

In the final section of the exhibition, the dancing models I had glimpsed at the beginning were now bigger and closer, their braids and twists swift and mobile as they bounced and posed for their hidden friend behind the camera. John Cena rapper Sho Madjozi’s interpretation of the Xibelani (a traditional XiTsonga skirt) stood alongside the elaborate, patterned two-piece Tokyo James suit worn by Nigerian singer Burna Boy. Here, we were firmly positioned in the present of fashion in Africa, where artists and celebrities model creativity and luxury, just as in the rest of the world.

It was a grand, swelling conclusion. I was taken aback by how much I was reminded of home; the bright lights of a bustling and ever-expanding Sandton. I thought of my peers and the multiple, yet somehow balanced co-existence of African identities that continues to confuse many, including our parents’ generation. The unending creativity, hustle and space-making that takes place within this organised chaos.

Image Courtesy of the V&A Museum

Familiar names came up; I felt the warmth of recognition when I saw my tribe represented in MaXhosa Africa’s modern interpretations of IsiXhosa traditional colours and patterns; the familiar divination mat onto which designer Thebe Magugu threw bones and turned his ancestors’ message into a two-piece garment in his AW 2021 collection, titled Alchemy. Lukhanyo Mdingi, whose work consolidates a history of craftsmanship with modern design, has continued his exploration of collective movements and creative labour in fashion. The ensemble from his Perennial AW 2019 collection pays homage to the history of South Africa’s mohair trade.

Minimalist forms – so rarely read as synonymous with African creativity – were represented by Rwandan designer Moses Turahirwa’s Spring/Summer 2018 collection titled Intsinzi, with an elegant pale blue top and pants as a contemporary take on traditional Rwandan dress. No form is as unifying and broadly familiar to Africans from each corner of the continent as the iconic checkered plastic Mas’goduke bag, otherwise known as the “Shangaan Bag” or “Ghana Must Go”, which made an appearance in Nkwo Onwuka’s Nkwo.

The African continent is just that – a continent. No story covering 54 countries can do them justice, but common threads were established. If Africa Fashion is a starting point – as it declares itself to be – then I am intrigued by what comes next in African storytelling at the V&A.

Image Courtesy of the V&A Museum

Notice: Function _load_textdomain_just_in_time was called incorrectly. Translation loading for the acf domain was triggered too early. This is usually an indicator for some code in the plugin or theme running too early. Translations should be loaded at the init action or later. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 6.7.0.) in /nas/content/live/fashunfilt/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6121

Notice: Function _load_textdomain_just_in_time was called incorrectly. Translation loading for the wp-migrate-db domain was triggered too early. This is usually an indicator for some code in the plugin or theme running too early. Translations should be loaded at the init action or later. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 6.7.0.) in /nas/content/live/fashunfilt/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6121

Notice: Function _load_textdomain_just_in_time was called incorrectly. Translation loading for the wpmudev domain was triggered too early. This is usually an indicator for some code in the plugin or theme running too early. Translations should be loaded at the init action or later. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 6.7.0.) in /nas/content/live/fashunfilt/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6121

Notice: Function _load_textdomain_just_in_time was called incorrectly. Translation loading for the wordpress-seo domain was triggered too early. This is usually an indicator for some code in the plugin or theme running too early. Translations should be loaded at the init action or later. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 6.7.0.) in /nas/content/live/fashunfilt/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6121

Notice: Function add_theme_support( ‘html5’ ) was called incorrectly. You need to pass an array of types. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 3.6.1.) in /nas/content/live/fashunfilt/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6121

In an intensely personal comment, Kiera McMillan, from Coventry, England, explains what it’s like to be working class and wanting to participate in the high glamour of modern fashion. She detects some signs of hope.

Confidence is the most valuable thing money can buy. For a lucky minority, it comes with education if you grow up in a comfortably-off family and have the fortune to be privately educated.

But that confidence is difficult to replicate if you haven’t grown up in such an environment, especially when it comes to navigating the elite spaces of the fashion industry. Imposter syndrome is a common feeling among students studying fashion.

Image courtesy of Osman Yousefzada

And then there’s the challenge of explaining your hopes for a career in the fashion industry to your father – in my case, an ex-coal miner whose understanding of fashion doesn’t extend beyond the pair of 30-year-old Levi’s in his wardrobe.

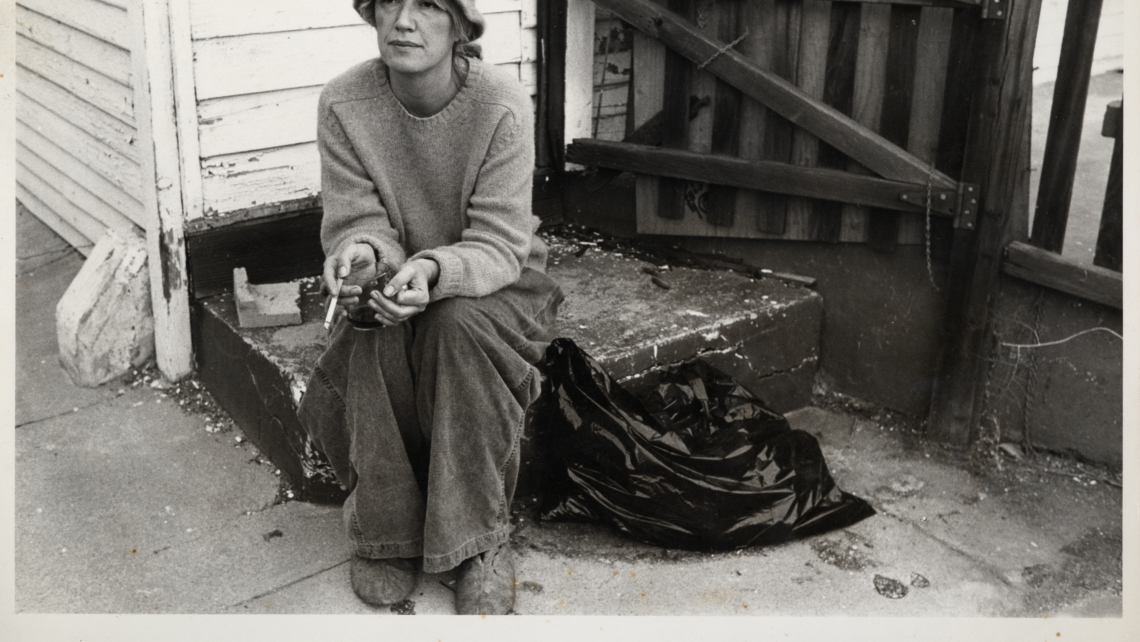

Growing up in a working-class family, luxury fashion always seemed so glamorous and out of reach. Then, abruptly, fashion changed tack and it became ‘cool’ to emulate your DHL delivery man (see Vetements, 2015) rather than the glitz usually associated with high fashion. For many fashion obsessives nowadays, it’s about replicating a ‘poor chic’ aesthetic, albeit at designer prices. Think Balenciaga Paris high-tops.

The appropriation of a working-class ‘aesthetic’ is nothing new to the fashion industry. References to working-class lives have regularly popped up on the runway. Back in the 1960s, a wave of working-class photographers and models swept into Swinging Sixties London and challenged a posh industry to respond to real lives rather than a pampered few. In design terms, the working wardrobe has been appropriated and carved up by any number of designers over the decades. Consider the year 2018, when Prada featured ID badges as accessories in its Autumn/Winter collection, while Calvin Klein, then designed by Raf Simons, made use of a faux fireman aesthetic.

Image courtesy of Osman Yousefzada

An obsession with workwear and the service industry is an appeal to the everyday through appropriating uniforms. Consider how Demna’s SS 2018 collection for Vetements features the stereotypes of delivery man, tourist, security guard and pizza delivery boy. Heart-felt? I’m not sure: to me, it came over as a mockery of the service industry, portraying workers as caricatures.

Designers who try to appear more ‘accessible’ to a non-luxury market of consumers miss the point. If I wanted to wear scrubs as a fashion statement, my first port of call wouldn’t be Prada SS 2011. My sister, who is a nurse, didn’t recognise the ‘minimal baroque’ intended by Miuccia Prada. She called it “nurse chic” but urged Miuccia to “smear some blood over it to make it more realistic”.

Image courtesy of Osman Yousefzada

Nurses were never the intended demographic – their salaries are far behind the models on Prada’s runway. If high fashion wants to be truly accessible, then it must be affordable, accessible and authentic. A good start would be to bring working-class creatives into more design teams, reflecting a sense of the ‘real’ world rather better than so many modern-day design teams that seem to live in ivory towers divorced from real-life economics.

Research suggests only 16 per cent of people in creative jobs in the UK are from working class backgrounds. As many as 80 per cent of journalists are from relatively privileged backgrounds. If these figures are even remotely accurate, then our knowledge and understanding of fashion are being communicated to us by a singularly privileged group.

Image courtesy of Osman Yousefzada

These figures become less shocking when we consider the frameworks that operate within the fashion industry. Top of the list are unpaid internships. To gain access to the exclusive world of fashion without industry connections or family connections, internships offer hope of a foot in the door. However, the intensive (and occasionally exploitative) nature of many internships, coupled with a lack of pay, means they’re taken up by those privileged enough to forgo a steady salary. The fashion industry claims they are gaining useful insight and experience. But who is really benefiting from this free labour?

That’s why it’s so important to celebrate and acknowledge the working-class talents who are shaking things up from the inside. I see some signs of hope. To take one example: Osman Yousefzada, a visual artist, designer, writer, and social activist from Birmingham, in the Midlands. His memoir, The Go Between, is a critically acclaimed account of growing up in 1980s Birmingham in a closed Pakistani migrant community. Drawing inspiration from his own life experiences, Yousefzada launched his label, Osman, in 2008 in which he explores the many facets of his identity through design.

Yousefzada’s most recent collection, for Autumn 2022, has a cast comprised of brown queer activists such as Parveen Narowalia, Ryan Lanji, Deepanshu Sharma, Anita Chibba and Sheerah Ravindren. With its fringing, voluminous ruffles and fuchsia feathers, this collection sidesteps the conventional glamour of high fashion.

Image courtesy of Osman Yousefzada

Instead, his pieces are interwoven with the narratives of Yousefzada, his cast, as well as the artisanal makers, weavers and embroiderers in India who produced many of the garments in partnership with the designer. Yousefzada’s efforts to give space to new narratives are not limited to his designs. His first short film, Her Dreams Are Bigger, aired in 2018 and shines light on the dark side of fashion by documenting the realities of fast-fashion garment workers in Bangladesh.It’s tough out there. But designers such as Yousefzada are setting new standards for innovation and authenticity. It’s almost enough to make me feel confident.

As a post-pandemic culture takes shape, one trend is re-emerging. A new wave of designers, image makers and communities are embracing gorpcore – including outdoor active looks and the activities that they’re designed for. In short, out is in.

Outdoor equipment and clothing companies, including Arc’teryx, Asics, Klättermusen, Nike’s ACG and Salomon, are trying to take the stylistic and cultural lead through collaborations, sharing the design credits with emerging collectives such as Athene Club, Flock.Together and GORPGIRLS.

Founded to protect nature, diversify greenspaces, champion the outdoors and bring communities together, these collectives are out to promote change, one adventure at a time. They’re collaborating with outerwear brands to offer sponsored opportunities and experiences in nature. Conscious creatives are conceptualising immersive, original and considerate visual content that showcases breathtaking terrains while putting equipment to the test.

The trend is reinforced through nature-focused Instagram accounts (such as @unownedspaces, @hikingpatrol and @114.index) with huge online presences. Content spreads through cyberspace at hyper-speed.

Coined by The Cut in 2017, Gorpcore fuses normcore with gorp, an acronym for the colloquial term for trail snack favourite, Good Ol’ Raisins and Peanuts. It describes a utilitarian style centred around practicality and functionality. It’s about a low-key wardrobe of staple pieces, discreet enough to fit into a compact backpack, that is worn time and time again.

Designed to compete with harsh weather, pieces are built from high quality, lightweight and weather-proof technical fabrics. Fits are loose for ease of movement; pockets and belt loops feature heavily to keep things close on the go. Reflectives increase visibility in adverse conditions. Colour schemes vary from earthy tones to vibrant hues depending on the purpose of the garment. Being noticeable is a given for safety in the mountains.

Many outerwear brands have long centred on nature. Patagonia is famous for its environmental action, donating 1 per cent of its annual income to environmental non-profits around the globe. Meanwhile, 94 per cent (and counting) of the brand’s products are made from recycled and renewable materials. Patagonia says ‘carbon neutral is not enough’ and promises to use its influence to meet the climate challenge with systemic change. Arc’teryx, Klättermusen, The North Face and Kathmandu are also making efforts to protect the planet.

The gorpcore trend has rapidly moved onto city streets. Ben Maher, founder of London-based designer and sportswear resale company PastDown.Store, reports that Arc [‘teryx] jackets, vintage ACG and Montbell pieces are selling out rapidly, adding that there is “a real scene for hiking gear at the moment”.

Searches on Lyst, the global shopping platform, reflect the trend. In late 2021, searches for pieces like the Arc’teryx Beta AR jacket, Patagonia zip-up fleeces and Salomon technical sneakers hit an all-time high, says Brenda Otero, formerly culture communications manager at Lyst.

Saeed Al-Rubeyi, co-founder of UK-based planet positive streetwear brand Story mfg, reflects on gorpcore. “There is a strange thing that is happening where dudes are dressing like they’re going on an expedition to the South Pole when actually they’re just going to Carnaby Street. The good thing is it’s got people more into outdoor gear. The bad thing is that everyone feels like they need an £800 jacket to go down a country lane when they could wear anything that they wear to the pub.”

As street style diehards catch wind of gorpcore, they naturally want to test out their new gear in the big outdoors. “People want to trial the functionality of their new outerwear, immersing themselves in the home of gorp gear, away from the churning cogs of the city,” says Maher. “The more immersed in nature we are, the more inclined we’ll be to make sustainable choices. Fashion-related or not.”

Al-Rubeyi agrees. “Exposure to the outdoors is always good. It’s good for your health. It’s good for you. Seeing something first-hand is always more powerful. If you see something beautiful, you’re going to want to preserve it… People who spend more time outdoors seem to be much more connected with nature, the planet and wider issues such as sustainability.”

Young designers support the thinking behind gorpcore. “It’s great when fashion isn’t just made to help us in nature but is also made to encourage us to engage with it. Great outerwear will push the wearer to face the forces of nature that are available, and through this, appreciate nature’s priority over us,” says menswear designer and Central Saint Martins graduate, Jimmy Howe.

Nature, quality and sustainability form the foundations of many emerging designers’ work. Howe finds that “nature and fashion fuse from usage and the need for protection against the elements. There is sustainability in longevity. I really hope this is something that is drawn from the ongoing appreciation of outerwear. Some of these jackets are made so beautifully, their attributes are what I would define as ‘luxury’ and their usability reflects their sustainability.”

He adds: “The planet cannot function anymore on single-use products like plastic bottles, straws and food packaging, as much as it cannot survive any longer with single-use clothing. The idea of buying something, no matter how it was made, to just wear it once, or once a year, is destructive. Pieces derived from functionality offer us incentive other than to just look good once.”

Arnar Mār Jōnsson and Luke Stevens, the Icelandic-British duo behind high fashion-outdoor fusion brand Arnar Mār Jōnsson, share a similar mentality. “Using nature as an element in all of our design processes makes it hard to overlook all the damaging factors that fashion is having on the environment,” says Arnar Mār Jōnsson, who graduated from the Royal College of Art in 2017.

Mār Jōnsson and Stevens are in search of natural alternatives to the harmful synthetic and plastic materials previously used for outdoor garments. After exploring the heritage of Icelandic cloth, the duo decided to work with Lopi, a water-resistant and insulating knitting wool made from the fleece of Icelandic sheep. They also experiment with plants to make natural dyes.

“If more brands start to think in such a way, this could have a positive impact on the products people are producing and their impact on the environment,” says Mār Jōnsson.

Fashion brands such as Jil Sander, Gucci and Jacquemus are vouching for gorpcore in the luxury realm with high fashion-meets-technical wear collaborations – fit for the metropolis and for the middle of nowhere.

As environmental pressures become overwhelming, a rethink is unequivocal. Where aesthetics and responsibility once sat at opposing ends of the spectrum, the great outdoors is inspiring a fusion. Through creative output, continued collaboration and innovation, gorpcore can act as a catalyst for sustainable design and careful consumption. Long may it endure.

The British accessories designer talks about running a fashion brand in an age of ecological pressures and a constantly evolving consumer.

“It’s like a good game of chess – every day,” says Anya Hindmarch, designer and CEO of her eponymous label. She’s talking about running a fashion business, which she has done on and off for more than three decades.

Right now, she’s very much on. FashionUnfiltered collected the wisdom of Hindmarch at this summer’s Shoptalk Europe (June 12-14), a retail conference and exhibition staged at ExCel London.

Image Courtesy of Aya Hindmarch

Starting her business aged 19 after studying Italian in Florence for a year, Hindmarch (now 54) steadily expanded her self-financing business, building it to 58 stores in 10 countries. The Qatari royal family’s investment fund bought a controlling stake for £38 million in 2012, but Hindmarch took back majority control in 2019 after the brand ran up losses. Hindmarch has also found time to raise a family with husband (and colleague) James Seymour – they have five children.

Image Courtesy of Aya Hindmarch

Here are some of her thoughts on the fashion business and how she is re-engineering hers:

On the questionable value of fashion shows

After a run of high-profile runway shows in the brand’s early years, Hindmarch chose to scrap hers. “They didn’t feel that inclusive. The concern was – 20 minutes of big effort for the industry only, for invited people only.”

On the power of experience

In a digital world, retail has to engage to justify its existence. She references her Chubby Hearts project, first launched in 2018 as “a love letter to London”, with 29 giant inflatable heart-shaped balloons spread across the city. “It’s about the power of experience and the need of people to feel included.”

Image Courtesy of Aya Hindmarch

On going local

Picking up full control of her business in 2019, the designer instinctively knew, “I didn’t want to go back to the cookie-cutter stores around the world where it’s the same window display whether it’s Singapore or LA.” In 2021, she revamped her first store in London into The Village – a quintet of evolving concept stores on Pont Street, Belgravia. “It felt like a magnet,” she says. “Very authentic.” And the future of retail? “The next ten years are going to be about localisation, it’s going to be a real shift,” she says.

On returning to nature

“There is no waste in nature, no need for landfills,” she points out. That thought prompted the making of biodegradable bags in her Return to Nature colletion, launched in 2019. The big challenge for designers going forward? “How to design the end of life into the design of the product,” she says.

On innovation in fashion

“My approach is less about innovation,” she says. The focus is on refilling and reusing. Look to where fashion comes from, she insists. “Everything we buy and eat, and wear is farmed. Everything comes from soil – fashion comes from soil.”

Sustainability, she says, starts with “two words – common sense.” In an age of fads and a herd mentality, it’s important not to jump on the latest bandwagon. “Vegan leather? You think that’s a good thing? It’s not, it’s just plastic.” By contrast, leather can be “an incredibly smart way of using a natural resource… when sourced locally as a byproduct of the meat industry from a regenerative farm”.

On sustainability

Plastic should be kept in circulation, Hindmarch says. “It’s not about awareness. People are aware, it’s about what we need to do.” In early 2020, she introduced her I Am a Plastic Bag collection of cotton-canvas-feel bags, each made from 32 half-litre recycled bottles, launched at her Belgravia store with a display of 90,000 used bottles. The bags are designed never to be thrown away. “It you see it, you connect to the problem… [It’s] part protest, part art installation.”

Image Courtesy of Aya Hindmarch

On greenwashing

“Just be honest and tell your consumers the story,” she says. “Take people on the journey. Don’t greenwash if it doesn’t do you any favours. People can smell it. Say what you’re good at and what you’re not good at. By pretending or trying to be perfect, we’re doing ourselves a disservice.”

On purpose versus profit

“For all of us to put the environment on top of our agendas we need to not be worrying about the next meal,” she says. Hindmarch encourages all designers to refocus on the environment. “Once you start that journey, it becomes addictive.”

Realism is top of her agenda. “You can’t grow a business and completely reduce your carbon. Ultimately, we’ll have to reduce our footprint as much as we can.”

Notice: Function _load_textdomain_just_in_time was called incorrectly. Translation loading for the acf domain was triggered too early. This is usually an indicator for some code in the plugin or theme running too early. Translations should be loaded at the init action or later. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 6.7.0.) in /nas/content/live/fashunfilt/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6121

Notice: Function _load_textdomain_just_in_time was called incorrectly. Translation loading for the wp-migrate-db domain was triggered too early. This is usually an indicator for some code in the plugin or theme running too early. Translations should be loaded at the init action or later. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 6.7.0.) in /nas/content/live/fashunfilt/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6121

Notice: Function _load_textdomain_just_in_time was called incorrectly. Translation loading for the wpmudev domain was triggered too early. This is usually an indicator for some code in the plugin or theme running too early. Translations should be loaded at the init action or later. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 6.7.0.) in /nas/content/live/fashunfilt/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6121

Notice: Function _load_textdomain_just_in_time was called incorrectly. Translation loading for the wordpress-seo domain was triggered too early. This is usually an indicator for some code in the plugin or theme running too early. Translations should be loaded at the init action or later. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 6.7.0.) in /nas/content/live/fashunfilt/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6121

Notice: Function add_theme_support( ‘html5’ ) was called incorrectly. You need to pass an array of types. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 3.6.1.) in /nas/content/live/fashunfilt/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6121

Beauty entrepreneur Eva Alexandrides of 111Skin talks skincare trends, growing up in Bulgaria, and the myth of having it all

Eva Alexandrides, co-founder of hot London-based premium skincare brand 111Skin, is wearing a ruffled black blouse and high-waisted skinny jeans synched with a chocolate brown Louis Vuitton belt. She stands relaxed in three-inch heels, her thumbs hooked into her jeans. She looks poised, composed, perfectly put-together. But when I ask her if it’s possible to buy perfect skin, she doesn’t hesitate. “No!” she says. “Perfect is out of fashion. Be yourself!”

Her candid nature is the result of a past she describes as a “very dramatic journey”. Alexandrides, now in her late forties, grew up in socialist Bulgaria. She talks of her childhood fondly, despite living in a restricted environment and lashings of Soviet propaganda. She had developed an international outlook thanks to her mother’s job as an air hostess. She also inherited her mother’s interest in skincare and was excited to see the products she brought home from abroad, Alexandrides was also inspired by her mother’s meticulous dedication to looking immaculate.

Leaving a school where even nail lengths were monitored, Alexandrides took advantage of the opening up of Bulgaria in the Nineties and landed a scholarship to study in San Francisco. The move from Sofia to UC Berkeley, which she describes as “the most liberal institution in the world”, was a culture shock, to say the least. “One of my classmates used to come naked to school – because she was allowed, because she had the right to do that.”

Alexandrides, who remains fiercely proud of her Bulgarian roots, thrived in a more liberal environment and, after meeting her Greek husband, cosmetic surgeon Yannis, who had studied at the University of Miami. She moved with him in 2001 to London, where he started up his practice on Harley Street – at number 111.

From the beginning, Yannis, who is co-founder of 111 Skin, offered the option of non-surgical treatments, which was considered to be somewhat revolutionary in the world of cosmetic surgery. He does, of course, still offer surgery – “at this moment he probably has someone in the operating room, under full anaesthesia,” she laughs – but his fundamental philosophy hasn’t changed. He remains cautious about doing any procedure that might be replaced with a product instead.

Image Courtesy of 111Skin

It was Alexandrides who saw the true potential of the remarkably effective formulas devised by her husband – including an eye cream that was so good it convinced a patient forgo surgery – and she convinced him to develop a skincare line. “I think it’s very, very important to have experts that can give you the wider span of opportunities. That’s why we’re so, so excited with the skincare – because skincare can go really far if you have the right regime.”

Alexandrides’ hunch proved spot-on. An early marketing strategy – prepping models’ skin at fashion shows (including Christopher Kane and Roksanda in London) – successfully struck a chord with the bare-faced beauty trend. Business was further bolstered by the heightened interest in skincare over the pandemic. 111Skin has now achievedcult status. Actress Margot Robbie raves about the brand’s Bio Cellulose Facial Treatment Mask. The Celestial Black Diamond Facial is a must-have for supermodel Bella Hadid. The dewy skin seen at Victoria Beckham’s shows is thanks to Alexandrides’ team.

Observing her immaculate composure, I wonder how she manages it all while bringing up two sons in central London. “The way I balance it is, actually, I spend less time with my friends,” she says, speaking frankly. Alexandrides recognises that her business needs her as much as she can give as it gains momentum – even if that means her social life taking a hit. Family remains her priority: her boys have even charmingly featured in some of her 111Skin campaigns, posted proudly on her Instagram. Working with her husband gives them quality time on business trips together, but she is thankful they don’t share an office. “Or by now we would probably be divorced,” she jokes. “So, it’s my children, my work – and then my friends.”

Her brand is growing rapidly along with the skincare market itself – surging year-on-year and forecast to be worth $188 billion globally by 2026. What are her best insider skincare tips? Surprisingly, she recommends keeping it simple. “We have identified that you could have a very good skincare regime with a three-step routine,” she says. She recommends a cleanser, serum and a day or night cream. She emphasises that the important point is to use a product that makes you feel good – whether that’s a drop of hyaluronic acid a day or indulging in everything from exfoliator to eye cream.

Alexandrides, just like her husband, doesn’t advocate spending all your time and money on beautiful skin. In her opinion, positivity and a big smile are just as important. As she puts it, “If you’re positive, and if you have a good attitude, people are not going to look at you and say you have wrinkles.”

I’m out at Romford, on the fringes of east London, attending a BMX event run by a collective named We Were Rad. Freestyle and bunny hop competitions are underway: these tricks were not as easy I thought, and the finale, a celebration of pristine, carefully curated bikes which attendees had gone out of their way to bring, was almost a style within itself. The rider and their bike – the pride is unmatched.

Remember BMX? Think young American kids in the 1980s. Think Steven Spielberg’s E.T. Shell-suit jackets and children running around without parental supervision. Those were the days. And yet, here I am in 2022 out in Romford, full of enthusiasts of all ages and genders. Time for a revival, anyone?

In the 1980s BMX rose to the forefront of British youth culture. The bike became a must have for British teens, celebrated in magazines like BMX Bi-Weekly. That’s the kind of energy that the We Were Rad collective are seeking to recreate. It’s co-founded by a somewhat unusual trio of Clint Pilkington, a solutions architect; Andrew Rigby, a nurse; and Antony Frascina, a primary school teacher.

The BMXing of the 80s encompassed more than just the bikes. It became a youth phenomenon that drew on fashion, music and collective identity. BMX and its fashions existed in a symbiotic union. In an interview with the Museum of Youth Culture, Antony Frascina reflects on fashion’s role within the BMX sphere and its importance in celebrating a joint identity: “It began with the B Boys breakdancing in Sergio Tacchini suits. Then came the rise in casual culture where brands like Farah and Pringle thrived, before the late 80s saw skate punk dominate, placing international brands like Fila and Ocean Pacific at the forefront. [This] concluded at the end of the BMX craze with the early days of 90s rave culture, allowing street brands like Stussy to become staples of a collective youth style.”

Steve Gartside recalls his first Adidas tracksuit, Farah pants and Tacchini trainers, key brands of the casual era. Luke Haralambous “begged my old dears [parents] to buy me some BMX Clothing”. Marc Bellamy confesses: “To be Rad you have to have had Vans”, while Jay Hardy rates Vans as “symbolic of an alternate identity in the 80s”.

And then there was the music. Grant Stone says, “BMX and music all merged into one”, recalling a youth building ramps with boomboxes blaring. Andrew Rigby says: “The one song that will forever be associated with BMX is Hello by Lionel Richie. It was playing on the radio when my Dad went to pay for my bike”. Doug McCathy preferred punk – “music to ride hard and fast to”.

The subculture transcended the streets, attracting sponsorship from watch brand Swatch, which draped a giant Swatch over the barn behind the ramps. Grant Stone recalls his love for the brand Life’s a Beach because it sponsored his BMX idol Rick Johnson. Although the success and prominence of the bike are long distant memories, many still crave the nostalgic and collective identity it symbolised. A time without worries, good music and good clothes. Many teens would meet in their spare time to learn new tricks, discuss trends and simply enjoy being young.

Now We Were Rad has brought all those memories back with a book, self-published and collated by Pilkington, Rigby and Frascina – a five-year labour of love with 450 pages of images and information about the subculture. It’s a true bible of old school BMX, detailing the history of BMX in the UK in the 1980s, told by the kids that lived it. The book has struck a chord, featured by the BBC, the Museum of Youth Culture and Paninaro magazine. Esta Maffrett, writing for the Museum of Youth Culture, describes the book as “capturing the spirit of riding on your bike through a hazy summer afternoon in an English suburb”.

Demand for a BMX revival is certainly brewing. Milton Keynes, to the north of London, is a popular destination for BMX fans, while the Laces Out festival, focused on sneaker culture, is another key annual event in England. The success of British BMX Olympians – Charlotte Worthington, Kye Whyte and Beth Shriver – at Tokyo 2020 has also piqued mainstream media interest.

I watched the passion and love of those participating in the event in Romford. It was so refreshing to see a shared collective joy that transcended age, gender and bias. I’m now contemplating getting on my own bike again – although I’m 22, born long after the 1980s’ BMX scene passed on. It would certainly be wonderful to see the revival of this collective youth culture. Maybe, after all these years, we are still rad.

American fashion designers need to make more noise on the global stage if they are to progress. The Met Gala might have been a good place to start.

Now the dust has settled, it’s worth reflecting more deeply on the Met Gala in early May. Where, oh where, were all the American designers? As an American fashion journalist, I found their absence deeply disappointing.

Compared to France, America came late to the global fashion scene, an historical fact that perhaps has complicated its status to this day. The Met Gala actually covered two events – the first held in September last year, the second this spring’s ball – to mark the Costume Institute In America fashion exhibitions. It appeared that the purpose of fashion’s answer to the Superbowl was to highlight the rich fashion history of the United States and celebrate a new emerging generation.

But instead of shining a light on the unsung heroes of American design, the biggest names that had everyone talking were the usual big brands: Louis Vuitton, Versace, Prada, Gucci and Burberry. On both nights, notable and emerging American designers should have been at the forefront, but there were hardly any to be found.

On arguably the biggest night in fashion, how does the community reckon with this snub? This was an occasion to give up-and-coming American fashion designers their big break. Perhaps the problem lies with the Metropolitan Museum’s refusal to fund The Costume Institute budget (despite its annual exhibitions that draw millions of visitors). Thus, Anna Wintour, who chairs the Gala, is forced to work with the big fashion houses that fork out over $200,000 to buy a table – way beyond the budget of smaller designers.

But that’s not the whole story. Anna Wintour, a figurehead for the global fashion industry, and Tom Ford, chairman of the Council of Fashion Designers of America and Honorary Chair of the 2022 Met Gala, could do more to bring American designs into the conversation. It was a touch disappointing that Wintour wore a custom Chanel dress to the gala in May, not particularly on song with the ‘Gilded Glamor and White Tie’ theme reflecting America’s Gilded Age (1870-1900). Ford at least acknowledges that the Met Gala is not what it used to be. “The only thing about the Met that I wish hadn’t happened is that it’s turned into a costume party,” he’s said recently.

Over the years, the Met Gala has strayed further from its themes and has become an opportunity for Italian and French fashion big-name houses to market their ready-to-wear lines. Add to this the brand contracts that celebrities and models have obligations to fulfill – often they have little say in what they get to wear.

That’s not to say many of them didn’t look fabulous. Let’s take one superstar – model Kendall Jenner. Check her out in custom black tulle top with net embroidered overlay and black voluminous double silk satin skirt with hand-pleated ruched details. American designer? Sorry, no – it’s all Prada, right down to her leather triangle handbag.

Say, instead, Kendall had dressed American and the Met Gala had invited the CFDA Vogue Fashion Fund finalists to interpret the theme and showcase their skills to the public. Anna Wintour stated that this year’s class of 2022 finalists “represent the very best of what America can be – and what it can stand for”. Vogue featured Kerby Jean-Raymond of Pyer Moss in its September 2021 issue, but his clothes were nowhere to be found at the Met Gala.

And there’s more. Prabal Gurung, Christopher John Rogers, Head of State, LaQuan Smith, Peter Do, Coach, Ralph Lauren, Christian Siriano, Michael Kors and Area averaged two looks each. In totality, they equalled the number of invitees dressed by a single big European brand. Thom Browne was the only American to buy a table and bring a full crew.

The two–part exhibition is brilliant, as one would expect of veteran curator Andrew Bolton. The first part, In America: A Lexicon in Fashion, looks at the modern vocabulary of American fashion and defines its attributes. The second part, In America: An Anthology of Fashion, looks at its complex history. It’s a triumph. Which makes the low-key contribution of American designers to the Met Gala all the more disappointing.

This is not the first time American designers have been overlooked by the larger industry. A media favourite topic over the years has been the “death of NYFW”. Despite this notion, New York Fashion Week is currently enjoying a revival with critically acclaimed emerging American designers such as Kerby Jean Raymond, Telfar Clemens, Peter Do, Christopher John Rogers, Elena Velez and Connor Ives. They are forging paths of their own, creating new, more diverse identities for American fashion and doing so in a manner that is inclusive and mutually supportive.

While the Met Gala remains a symbol of the power of modern fashion in the world, its relevance for Americans, present and future, could fade if US designers don’t get more of a look-in. That would be one big pity – and a giant opportunity missed.

History was made, the results were thrilling but uneven. FashionUnfiltered’s first Metaverse Editor reports from the very first Metaverse Fashion Week in Decentraland

The first Metaverse Fashion Week, staged March 24th to 27th, has prompted intense debate in fashion circles. Watchers of the web3 fashion space fell into one of two camps: the incredibly enthusiastic, who were excited by what they saw and recognized it as a giant leap forward for fashion, and those who were more sanguine, patiently trying to make sense of this new metaverse thing.

Hosted by Decentraland, a “decentralized virtual reality platform”, Metaverse Fashion Week was an engrossing flurry of virtual activity distinctly uninterested in answering questions beyond those that would help guests buy or sell virtual wares.

Refreshingly inclusive and apolitical vibes could be felt everywhere. In a real world beset by economic strife and military conflict, there was a sense of escapism for the fashion crowd in attendance. Perhaps a touch of escapism is exactly what we need in these trying times.

It’s easy to get lost in Decentraland, or DCL, as it’s typically known. That’s not because of its immersive graphics, but rather because of its daunting size. Wanting to avoid looking like a total idiot, I logged in early to get my bearings, but quickly realized that technological learning barriers weren’t going to be an issue. It seems the rumors were true: maybe the Metaverse could really be accessible to anyone with internet access.

A two-piece ensemble from the Etro catwalk

I’ve spent way too many hours playing online open world games in my life, so I was more than a little disappointed by the appearance of the virtual environment. My avatar couldn’t actually do anything, other than walk around and chat with other users or click on virtual billboards, NFTs and links to a few Discord channels. A decentralized social platform managed and built by its users may sound cool, but in its current iteration Decentraland still feels like a sea of traversable ad space that needs to be purged of its crypto bro overlords.

But let’s focus on the fashion. From day one, it was clear that all the avatars in attendance were here to check out the clothes – and the clothes only – and not to prance around virtual medieval towns or flush excrement-shaped NFTs down virtual toilets. (Yes – that’s something I wish I could unsee.)

And the clothes were great: they seemed to have magical powers, inspiring a feeling of hope for the fashion industry’s future, a sense many of us have not felt in a long time. New narratives and new ideas emerged among digital folds of garments, even if they seemed ripe for release from their clunky and awkward forms. This is not to insult the designers, just to recognize that the digital fashion industry and the technologies that support it are still in their infancy.

Party like it’s 2099: look closely to see CWETEK#5671 wearing head-to-toe Tribute Brand

IRL labels like Dolce & Gabbana, Phillip Plein and Etro hosted shows, to varying degrees of success, at a catwalk built in a stadium-style digital building that seemed to outshine the garments as they came down the runway. D&G showed futuristic suits and dresses worn by animals: think Fantastic Mr. Fox attends a session on intergalactic trade policy in the 23nd century. Etro’s collection of resortwear in classic paisley prints – presented here in DCL for the first time, but also available for purchase in physical form – were ill-suited to low-resolution graphics and the prevailing big impact ethos of MVFW.

In truth, the clothes shown by real-world labels in Metaverse Fashion Week were overshadowed by the new digital fashion houses. Three labels already well-established in the digital world stood out: Tribute Brand, Placebo, and Auroboros.

Tribute Brand, which describes itself as a “platform for contactless cyber fashion”, released a limited-edition collection of wearables “inspired by Tekken’s Devil Jin and GTA’s ladies of the night” at the first official MVFW afterparty. The party brought out the DCL fashion elite, who showed up dressed to impress in dazzling digital looks. Some were wearing the looks just dropped by Tribute, including a bikini top, a micro miniskirt, thigh-high boots with matching gloves and a hairstyle with devil horns. The hairstyle was on sale in the marketplace for around 600 MANA, the DCL’s digital currency and the equivalent of £1,200.

Placebo’s retail space in DCL: pulsing techno beats and uber-cool clothes

Digital fashion house Placebo has a permanent storefront in DCL. Its signature aesthetic (“ageless, sizeless, genderless tech-couture”) mixes cozy puffers with a slick, liquid-like cyber-latex “fabric” and muted all-over logo prints. The style fits perfectly with the fashion landscape of 2022 and feels like the future at the same time. As garments that can be photoshopped onto images – rather than the blocky wearables worn by avatars in DCL – their looks are so enticing, they made me wish they existed offline just so I could touch them.

Auroboros hosted the closing event of MVFW, promoted as an immersive concert experience, in collaboration with Grimes. The concert took place in the impressive Auroboros store, a towering spire with plenty of space to showcase intriguing nature-inspired garments. Highlights: gravity-defying spikes, shimmering stripes that pulse and slither around the body, and translucent layers that show the “veins” of other garments underneath.

Auroboros take full advantage of the fact that designing for the virtual world doesn’t need to be anchored in gravity or time, but it also makes physical garments that are deeply rooted in the natural world: bespoke couture designs literally grow on the bodies that wear them, undergoing a crystallization process that takes six to 12 hours. That might just be the coolest thing to happen since Hussein Chalayan’s garments started shapeshifting for his One Hundred & Eleven show of 2007.

So was Metaverse Fashion Week a success? The answer is complicated. Errors abounded, with shows starting late due to technical difficulties and a lack of cohesive communication from event organizers. As my avatar was strolling around DCL’s luxury district, which is sponsored by NFT marketplace UNXD, I picked up a disappointed comment: “Really? Is this supposed to be the future of fashion?”

I understand the frustration, but the creators behind Metaverse Fashion Week aren’t the ones to blame. Sometimes, the hype and obsessive marketing push behind the metaverse seems disproportionate to how much of it has already been built – which is essentially none of it. Metaverse Fashion Week was supposed to be about clothes, not a discussion on digital infrastructure, but it can be very difficult to separate the topics from each other at this early stage when everything is still an experiment.

An exchange between two partygoers at the closing-day event sums up my take:

“NGL this is disappointing!! No way this is supposed to be a historic moment. Grimes isn’t even playing live. And where are my free NFTs??!”

“Dude… please just shut up and enjoy the show.”

Unpicking Menswear: the V&A’s Blockbuster New Show

The V&A’s first major exhibition on men’s fashion sets out to unpick menswear, and men, at the seams. Tony Wilkes works out what it means.

What is the freedom that so terrifies men that they continue to say nothing, to devise nothing? To come up with no new or original discourse or critique about their own condition?

When do we get men’s liberation?

– Virginie Despentes, King Kong Theory (2006)

Men’s sartorial liberation first came to Britain on Carnaby Street in the 1960s. Young men stopped looking like their dads, stopped wearing wool and tweed, and wore paisley prints, shantung silk, a colour palette of pinks, purples, oranges and reds, nipped-in waists, tight, tight pants. Carnaby Street, said critic Nick Cohn, “sold stuff that could once have been worn by no one but queers.”

All this and very much more is celebrated at Fashioning Masculinities: The Art of Menswear, the V&A’s first major exhibition on men’s fashion. Bringing together some 200 looks and artworks, the show is “a clarion call for us to unpick masculinity at the seams and examine the very stuff it is made of,” according to Tristram Hunt, director of the V&A. Co-curated by veteran Claire Wilcox, Rosalind McKever and Marta Franceschini, it runs until November 2022.

Walk into the first of three sections, Undressed, and read the text on the wall – it’s about men’s bodies, how menswear has mimicked classical ideals. You see all these statues and clothes all in white and already you’re thinking, what the f**k does this mean and what is a man and what does all this – a naked trompe-l’oeil Gaultier blazer and Warhol nudes and a wrestler flexed in a bra – what does this mean to men in the street? Men’s version of shopping is still, broadly speaking, going to the gym. Their clothes are their muscle. You want to look all Farnese – I mean the Roman statue of Hercules from the Villa Farnese, totally ripped. Which hints at the irony at the centre of fashion – all this time and money and effort on clothes, when the whole point, really, is to look so desirable you can’t keep them on.

Reviewing the show, fashion writer Charlie Porter makes a nice point about men’s jackets. The technical name for the bottom part, the big below the waist, is “the skirt.” Putin, James Bond, Malcolm X – most men, for all this time – have all been wearing “skirts.” Like all clothes, Porter wrote, men’s jackets are “just drag”.

But menswear has never been about drag fundamentally. It’s been about Being A Man. That – and Looking Rich. And what lies behind all this history, which the show deals with, is Being A Man means Not Looking Feminine. It’s a history of shunning effeminacy.

You see it in the catalogue. Writing on Gaultier’s sari suit (1997), Avalon Fotheringham, curator of the V&A’s Asia Department, explains that Indian dress, like the jama (flowing skirts made of lightweight cotton) was mocked by the British, pitching “civilised” and “masculine” Western dress against “uncivilised” and “feminine” Indian dress, to “control, disenfranchise and oppress Indians” under British colonial rule. The same effect is seen in Japan when, in 1871, the emperor reformed Japanese dress to bring it line with Western fashion, proclaiming: “We should no longer appear before the people in these effeminate [Japanese] styles.”

But that was then. In a quote that opens the show, plucked from Gucci’s AW20 press release, creative director Alessandro Michele says “In a patriarchal society, any possibly reference to femininity is aggressively banned, as it is considered a threat to a masculine prototype that allows no divergencies. The model is socially and culturally built. It seems necessary to suggest a desertion, away from patriarchal plans and uniforms. Deconstructing the idea of masculinity as it has been historically established. Opening a cage.”

In high fashion, menswear is moving closer to womenswear. This is the V&A vision. The show ends with a white wedding dress made of cotton, lace, organza, satin, plastic and rhinestones, designed by Ella Lynch and MistyCouture, and worn by Bimini Bon Boulash, a non-binary model and drag queen, on Ru Paul’s Drag Race UK (2020). The final look is the freedom that most men can’t face, summed up by Bimini when they sang: “Don’t be scared to embrace the femme, whether you’re he, she, or them.”

And so we come back to the “queers.” Fashioning Masculinities is almost entirely a queer exhibition. There’s a Hockney nude, a George Platt Lynes, the original jock strap from 1915, a film made by trans artist Cassils called Tiresias (2011), a man in Greek myth transformed into a woman, and that Bruce Weber ad for Calvin Klein.

We “queers” know. We fail automatically at Being A Man. We’re expelled. And being expelled, we find we are liberated. We see from the outside that Manhood is fashioned, so made.

Oscar Wilde knew, and was basically killed for it: “Truth is absolutely and always a matter of style,” he wrote. Fashioning Masculinities shows that Being A Man is only clothes-deep.

Why Eve Babitz Matters

The Huntington Library, California, has acquired the Eve Babitz archive. Tony Wilkes explains why the memoirist and fashion writer matters.

Virginia Woolf read Proust and wrote to Roger Fry: “Oh, if I could write like that! There’s something sexual in it – I feel I can write like that, and then I can’t”. Eve Babitz felt the same, not for Proust, but Colette. “Colette was like a concubine which fascinated me,” she said. “She made me want to be her and write like her.” I’ve read Colette and Virginia Woolf and four books of Proust but still. My Colette is Eve Babitz.

When she was fourteen Babitz started writing her memoirs, I Wouldn’t Raise My Kid in Hollywood. A few weeks before she’d been picked up and kissed by a man she’d never see again except on the front of the papers two years later when he turned up dead in Lana Turner’s bathroom. “I’d been writing that book sort of before that,” Babitz explains in her first book Eve’s Hollywood (1974). “After that, I’ve always been writing it.”

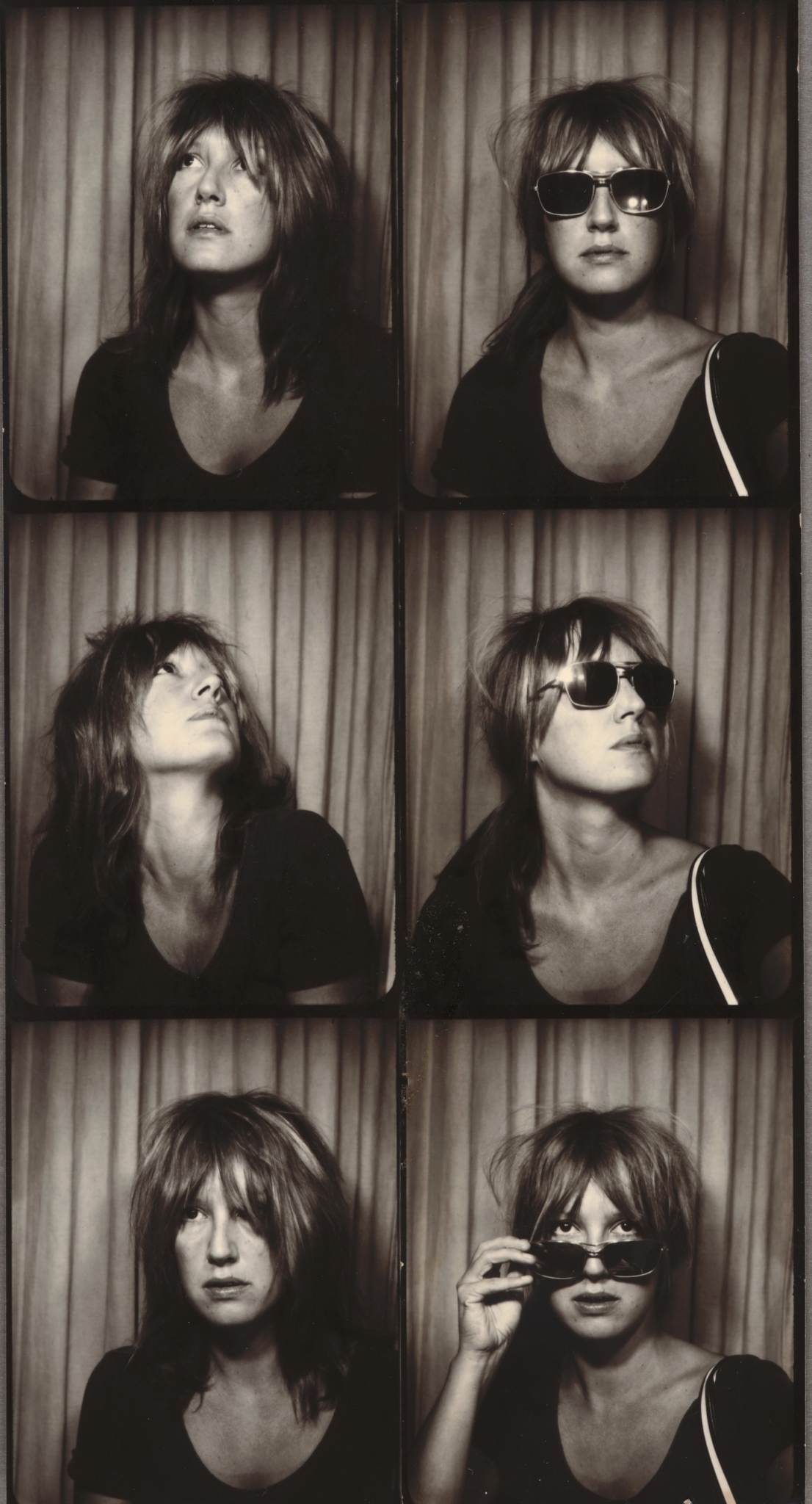

That book she turned into others: Slow Days, Fast Company: The World, The Flesh, and L.A. (1977), Sex and Rage: Advice for Young Ladies Eager For a Good Time (1979), L.A. Woman (1982) and Black Swans (1993), all memoirs or essays, though one’s called a “novel,” based on her life in Los Angeles. They were panned by critics. A reviewer wrote in the New York Times: “I discern the soul of a columnist, the flair of a caption writer, the sketchy intelligence of a woman stoned on trivia.” She fell out of print.

But by the time Babitz died last December, aged 78, all of her books were reissued. Some were bestsellers. Critics had written she ranked with Joan Didion. Following the reissue of her first book, in 2015, The New York Times ran the story: “The Eve Babitz Revival.” Her collected journalism, including fashion writing for Ms. magazine and Vogue, was published in 2019. Now, the Huntington Library in Southern California has acquired her archive, a collection of art, manuscripts, journals, photographs and letters spanning 1943-2011. There are 22 boxes, filled.

Babitz was born in 1943 to L.A. culturati. Her father was a studio musician. Her mother was an artist. “I looked like Brigitte Bardot and was Stravinsky’s goddaughter,” she wrote. Her skin “radiate[d] its own moral laws.” In Duchamp Playing Chess with a Nude (1963), Babitz is the Nude. The dedication to Eve’s Hollywood, running nine pages long, includes Warhol (who loved her tan), Joan Didion (“for having to be who I’m not”), the whipped cream at the Polo Lounge, and some guy named Derek Taylor: “Tell them, Derek, how great I am. Like you once introduced me to a Beatle as ‘the best girl in America.’”

In The Guermantes Way (1920), Proust describes some fictional memoirs written by Mme. de Villeparisis. It’s long but it’s relevant: “She had retained from the period in which she lived, and which she described with great aptness and charm, little but the most trivial things it had to offer. But in a certain book of memoirs written by a woman and regarded as a masterpiece, such and such a sentence that people quote as a model of airy grace has always made me suspect that, in order to arrive at such a degree of lightness, the author must have been imbued with a rather weighty learning and a forbidding culture.” You could swap Villeparisis for Babitz. He’s writing on Babitz.

Her airy grace and forbidding culture derive from the L.A. “Cool School.” Centred around the Ferus Gallery, founded in 1957, this group of artists led Art in America, in 1966, to report a “distinct L.A. sensibility,” an emphasis on “polished, slippery surfaces,” a kind of formal “hedonism.” Babitz, at the centre of this scene, wanted to write with a “finish so gorgeous” the work stands “away from ordinary life as an enamelled example of something handled as though someone cared, for once, for the form.” She wrote in Slow Days: “When the Ferus Gallery began exposing Los Angeles art in the fifties, people quickly observed that everyone seemed to be obsessed with perfection in L.A.”

And her prose is perfection. Writing in Eve’s Hollywood, Babitz writes of the Finish Fetish, an art that is glossy, glamorous, stylish, a style so widespread it became known as “The L.A. Look.” Babitz is a Finish Fetish writer, polishing her prose to a rhythmic smoothness. Compare “C.C.’s regular school clothes carried with them the same spirit as Monroe in “Niagara” combined with a whore of Batista’s Havana,” with a line from Lord Byron: “The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold; / And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold.” But Babitz stays casual, sliding by, careless, loose. You are gutted into silence, awed.

But critics don’t like surfaces. Especially ones that are made to look easy. Interviewed by the Archives of American Art in 2000, the transcript reads: “Well, you know what that implies—-?”, “That’s I’m a shallow person?” “No. No.” “I am a shallow person. I can be superficial because I know what I’m turning down.” What Babitz turns down is a reading that digs, that violates art to find meaning under the surface, hidden. For critics, “truth is the rapture of the deep,” Babitz wrote, “whereas to us the rapture of the shallows is more than enough.”

London Fashion Week: Best in Show for AW22

As the industry steps back onto the physical runway, the best of London Fashion Week’s designers dazzled with ingenuity. A sure-footed celebration of community, connection and talent.

With some major names not on the schedule, it might be assumed that London Fashion Week would lose its sparkle. Instead, emerging designers made an impressive impact across the city. Priya Alhuwalia and Connor Ives made their entry with debut catwalk collections, while 16Arlington honoured its late co-founder Frederica Cavenati. LVMH Prize nominee S.S. Daley explored sexuality and previous winner Nensi Dojaka celebrated body diversity.

Here’s our summary of the most interesting shows for Autumn/Winter 2022.

Conner Ives

Conner Ives made a brilliant debut on the schedule with a confetti cannon of Americana glam. His first physical show, hotly anticipated, was ablaze with celebratory verve. It crashed the Hollywood party girl trope with bling-spangled glitterball dresses, macramé tassels that poured down the leg like spilled champagne and tastefully tacky logo prints. The native New Yorker had graduated Central Saint Martins while the pandemic raged on – and now it was time to shine, groove and act debauched. titled Hudson River High, the collection lauded pop-cultural iconography and electric Y2K sleaze, headed by a trail of rainbow butterfly clips and slinky baby tees. Its fictitious roll call of characters played host to garish internet stereotypes and trash television alike. Out came the quirky cowgirls, Motown mamas, knock-off contestants from America’s Next Top Model and Jackie Kennedy in a sweeping A-line number.The Devil Wears Prada’s Andy made a bootleg appearance, no less.

On|Off presents Jack Irving

The ominous inflatable octo-tendrils at Jack Irving were somewhere between devilish deep-sea mutation, alien fetish nightmare and Slenderman subject to steroids. Perhaps, even, a parasitic critique on the pandemic. Either way the latex appendages, which swelled like bacteria, were a sight to marvel at and a credit to the designer’s background in costume design. Hailing from Blackpool, Irving infuses molecular theatricality with engineering to stir fashion’s functional core – you’ll find no ready-to-wear here. This performance saw models act out spike-shedding rituals, resulting in visual spectacles that were simultaneously viral in structure and social media presence. Urchin-esque limbs teetered above chromatic breastplates in a kind of ghoulish cabaret, with metre-wide balloons that might just consume their wearer in an unfortunate breeze.

Matty Bovan

Bovan’s back – and with souvenirs to show for it. Having spent last summer across the Atlantic with his partner, the Yorkshire-born designer uprooted any patriotic proclivity he held in favour of punked-up stateside memorabilia. Shredded and reconstrued varsity jackets star in the collection, with diced American football vests playing ball with dog-eared knit shawls. Re-cobbled Converse footwear was mixed with denim capes; then came windbreaker skirts runway – styling that very much speaks to a muddled, jumble-sale jollity. This is no deviation from Bovan’s usual cut-and-paste craft. Working from a home studio in past seasons, the designer concoct s the absurd from technicolour offcuts and his mother’s handmade jewellery. For this iteration, aptly named Cyclone, he drew on the whirring chaos caused by Covid-19, hence clothing that looks haphazardly clashed together, a curated wreckage.

S.S. Daley

Stately houses set the scene for Steven Stokey Daley’s menswear story, which navigated closeted sexuality through topsy-turvy, opulent interiors. Performers drafted in from London dance schools placed a queer slant on setting; some entwined playfully on a four-poster bed, other couples canoodled on the chaise longue. It embodied all the Old Money affluence of Downton Abbey under a new love-is-love impulse, decorated smartly by chequered suiting and silken pyjama coats. A front-running semi-finalist for the LVMH Prize, Daley is once again decodifying the world, not only through gender with a unisex cast, but also the English class divide, softening its rigid walls through ballet. Each look is tethered to humble tales from the streets; a cable knit jacquard reading “You and I are Earth” came from phrases etched on a plate in the London sewers. Elsewhere, modish waistcoats resurrect the hushed desires of dandyism and 17th-century shirts billowed teasingly atop loose trousers.

Nensi Dojaka

Nensi Dojaka won the LVMH Prize last year and has lingered in the limelight ever since for her contributions to svelte, lingerie-like dress. Full of spaghetti straps and sex appeal, the designer extended her net on body inclusivity, working her wisdom around wider hips and curvier busts – and, in so doing, broadening her appeal. Besides romantic, sheer ruchings that swaddled the stomach of a pregnant Maggie Maurer, the collection dialled up texture to embrace lustrous leathers and sequined panelling. Dojaka’s subtle take on lust intensifies body confidence for any and every woman, be that through bare-all bralettes or the slick cut of a blazer. Awash with earthy hues, this season featured bulkier shapes – a cropped puffer, voyeuristic leggings and erogenous and cut-out midi dresses.

Ahluwalia

Traversing a cultural confluence between Bollywood and Nollywood movies, Priya Alhuwahlia, like the rest of us, spent her lockdown soaking up films. After releasing five fashion films, cinema magic bled into her debut IRL show; a sumptuous, well-read tour of global tailoring, its artisan techniques all coloured in ochres and oranges like a fiery Saharan sunset. There were rich textures in the corkscrewed denims, the wispy satins, a patchwork collection that saw pinstripe twinsets and saris imitate mottled set designs and handpainted motifs lifted from poster ads. But there was also a deeper, visceral texture in the narrative. From her career summit, the fledgling designer waved a welcome flag for Nigerian and Indian traditions in honour of her mixed heritage. Earning myriad accolades, she’s most recently becoming a finalist for the Woolmark Prize.

Richard Quinn

Who let the dogs out? Richard Quinn unleashed his lurid latex gimps from a pink boudoir once more, slinking and squeaking at every step with a peverse eroticism. A human bondage pup was walked onto the runway by drag queen Violet Chachki, much to the pleasure of viral rubberneckers on TikTok. Gyrating below a grand candelabra to sways of a symphony orchestra, models in XXL vinyl lampshade hats, punchy florals and pumped-up princess gowns yanked over the head brought pride back to Britain, post-Omicron. This bevy of demi-couture was steeped in seductive, optimistic thrill: its caftans and swollen crinolines yearned to be ogled, not locked away in confinement. It was familiar in many ways, but repetition seems a sensible move when his flowery signatures have just been nominated for the BFC/Vogue Fashion Fund this year.

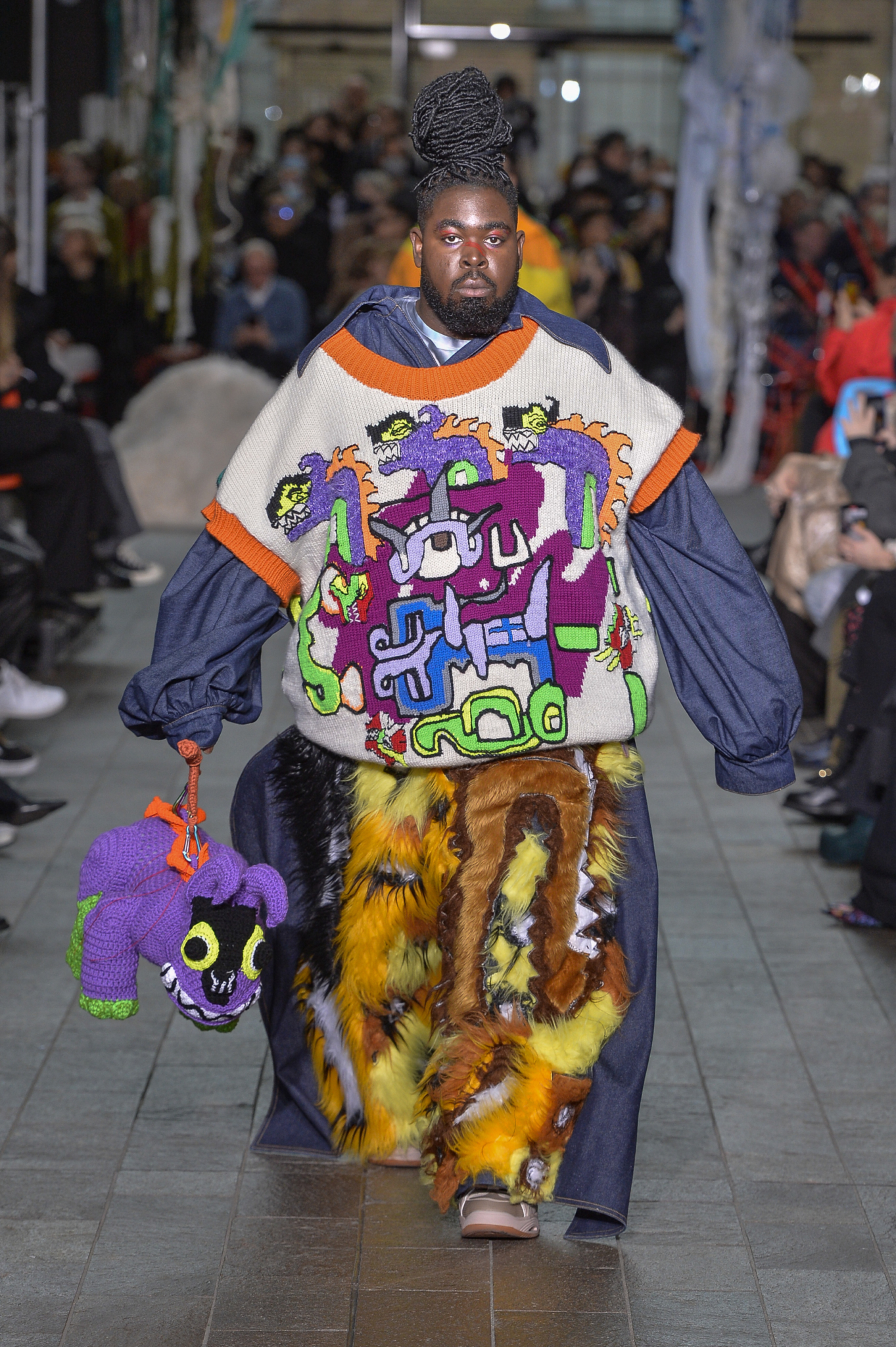

Central Saint Martins

School is a mixed clique for most. Within the illustrious Central Saint Martins, there are no Hulk-armed jocks, no geek clichés, but a whole carnival bonanza of art kids that provoke fashion’s playsafe ways. This year, they graduated with flying colours, notably Ed Mendoza who co-won the L’Oreal Professionel award with Jessan Macatangay for his plus-sized, Afro-Latinx garmentry in all shades of the rainbow. Among the 32 MA fashion designers showing, highlights included: Liza Keane, who sculpted her feminist vision from beastly anatomy, and Kazner Asker, who debuted hijabs in a notable first for the course. From Thomas Newbury’s boa-slinging glamazons to James Walsh’s flocked egg helmet, this was an event full of fun and intimations of the future of fashion.

16Arlington

“This one’s for you, Kiks,” read notes on the seats at 16Arlington. Co-founder Frederica ‘Kikki’ Cavenati passed away suddenly towards the end of last year. Upon her death, the Tears collection was completed by Marco Capaldo, the designer’s beloved best friend and business partner. The departure birthed a soul-capturing tribute with angelic white suiting that swept the floor, marabou necklines paired next to furry marshmallow hats and heaven-high clogs. Capaldo cultivated textiles from grief – recreating the accidental puddle-marks his tears left on the work desk into patterns imbued with Kikki’s vivacious flair. The show must go on, it said. As the final sequins shuffled into darkness, the audience rose in a deserved ovation.

Yuhan Wang

Yuhan Wang’s collection was dubbed Venus in Furs, from a book of the same title. The designer wanted to challenge perceptions as to what makes a goddess. How is divine perfection portrayed? Wang’s answer came in the form of cobweb latticework and soft tactility; lace stockings, emerald satins, tassel fringing that poured from asymmetric houndstooth hems like a waterfall. They washed away an old femininity for a new vision full of sophistication. Shell adornments, made from corn plastic, decorated models’ ears and necks, and the designer wove knits into her work for the first time, each jumper emblazoned with a cat jacquard to hammer home the message: “Sometimes we can be very cute, sometimes we can bite.” Meow!